Anna Scherbina (2008), then at the University of California, Davis, noted earlier research showing firms that performed badly were often reluctant to share negative news with investors. Frequently, the bad news was suppressed not only by firms but also by the securities analysts who covered them. Analysts could be pressured to withhold bad news both by the management of firms they covered and by their own employers trying to secure an investment banking relationship with those firms. When the disadvantages of reporting bad news outweighed the advantages, analysts prefered to stop issuing forecasts of any kind. She hypothesized that, because analysts faced no pressure to withhold good news, diminished coverage was likely to be associated with bad news.

To test this hypothesis, she used the I/B/E/S dataset of analyst earnings forecasts for U.S. firms. She sought to identify instances of reduced analyst coverage in this dataset. She compared changes in the amount of earnings forecasts relative to the number three months earlier. Using this measure, she reported a decline in analyst coverage in ten to thirty percent of the sample U.S. firms in any given month.

To check whether declines in analyst coverage contained negative information for future returns, she constructed portfolios of stocks based on whether or not analyst coverage had declined. She divided her sample into five equal parts (called quintiles) based on market capitalization. She found that stocks in the lowest and next lowest size quintiles for which analyst coverage had declined underperformed other stocks in their size quintile by 0.57% and 0.46% per month, respectively.

She further checked trading patterns of institutions. She hypothesized that if her measure of missing negative information truly captured unreported bad news, institutions would sell their holdings as this measure increased. She found that, overall, institutions did, indeed, reduce their holdings of stocks for which her measure of withheld negative information (a complex mathematical formula) increased.

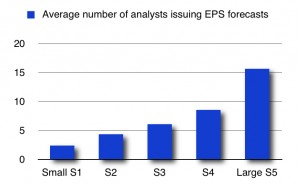

She concluded that, because both firms and analysts preferred not to report bad news, the absence of new analyst signals, on average, were interpreted as bad news. Not surprising, this finding held to a higher extent for smaller stocks. Fewer analysts cover smaller stocks, as the chart below shows. Therefore, the absence of new information from even one analyst would be more noticeable.

Using data from 2005, 3280 firms were divided into quintiles based on market cap. Firms priced at less than $5/share were excluded. Based on data from Scherbina (2008).

Trading strategy: Keep track of the number of analysts following the stocks you wish to trade. Avoid taking long positions in smaller companies when the number of analyst reports has declined in the previous three-month period.